A Short, Factual History of

The Old RailRoad With Carnival and Circus Trains

Railroad History of Carnival Show Trains and Circus Show Trains

By: “Doc” Rivera

The American circus is older than the country itself. The first circus troupe of record dates back to 1724 when a small troupe gave its first performance in an open arena outside of Philadelphia. The first complete circus performance is generally ascribed to John Bill Rickets who built an amphitheater in Philadelphia and gave his first performance on April 3, 1793.

President George Washington was an avid circus fan and attended Rickets’ Show on April 23 and 24, 1793. By the early 1820s, there were approximately thirty animal circuses touring the eastern United States. These shows moved at night by wagon, over country roads, often mired in mud. During the heyday of the railroad circus, these shows would become known as “Mud Shows” for obvious reasons. There had been an occasional attempt at railroading by a few of the early shows, but most went back to the wagons and country roads after only one season.

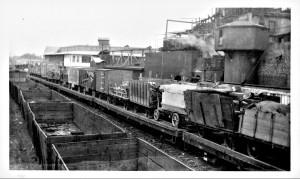

Eventually, the term, “railroad show,” became synonymous with large circuses and carnivals. In the early years, people began to think that if a circus or carnival traveled by rail, it had to be modern and big. A show that made the transition from a mud show to the rails had reached the big time. The railroad impacted the type of equipment carried by the various shows. Mud shows made every attempt to keep their wagons light and small in size, but the railroad show permitted the shows to increase the dimensions and weight of their wagons. After the penny conscious show owners filled the insides of their wagons, they modified the outsides to carry even more equipment. The wagons were further modified to include removal or flipping up of the wagon tongues used to pull the wagons to the show grounds so that they could get more wagons on a flat car. When the railroad show owner could no longer modify the wagon to carry more equipment, they modified the rail cars themselves. The circus and carnivals wasted no space on the railroad cars; extra tent poles, ride parts, and various equipment was stored either on the roofs of stock cars or under the wagons on the flat cars. Some of these early shows actually had so much surplus equipment crammed into and on the wagons that the sides actually bulged dangerously beyond the sides of the rail cars themselves. (see photo)

The railroads generally charged the show to haul their train in multiples of five or ten railcars. If a show consisted of ten to 35 cars, the railroad charge in increments of 5 cars; shows of forty or more cars were charged in increments of ten cars. So, whether the show train consisted of 16 or 20 cars, the owner was charged for a movement of twenty cars. Therefore, you will find that the length of most show trains were in multiples of five or ten. Before the days of trucks and tractors, when horses were the prime means of moving the wagons from the train to the circus lot, the train consisted of approximately 50% flat cars, 25% stock cars, and 25% coaches. A typical 20 car train of the time would consist of 5 stock cars, 10 flats, and four coaches. The fifth coach would be traveling ahead of the show as an advance or advertising car, perhaps connected to a scheduled railroad passenger train, but was still included as one of the 20 cars of the train.

The “Gilly” Show – Railroad History from Circus Trains and Carnival Trains

Two car railroad shows began around the 1890s. For many a fledgling operator, the introduction into outdoor show business was on a shoestring budget. Few could afford the initial outlay of money that was required to get a show of any decent size on the road. The “Gilly” show was entirely different in operation than the flatcar circus and carnival. These shows came to be known as “Two Car Shows” since that is exactly what most of them had, two railroad cars. Although the large flatcar railroad shows moved on their own schedule, the Two Car Show moved on regularly scheduled trains, usually passenger trains. They mainly consisted of a baggage car and a coach.

In the days of these Two Car Railroad shows, it was standard railroad procedure that anyone buying a specific number of first-class tickets, usually 25, received a free baggage car.

Even with the two-car railroad show that might own its own cars, the railroads operated the same way. Buy the specified number of first-class train tickets and the railroad moved the cars for free. Many a two-car show owner would buy only the required number of tickets but carry upwards of 75 people. These un-ticketed people would hide in possum bellies, any available compartment, and especially the baggage car until the conductor had received the tickets and counted the people on the car.

Frequently, the two car shows would rent a show lot from the railroad and set up adjoining the railroad cars on the siding. Most of these two car shows trooped as “gilly shows,” which meant that the show either hired local farmers with wagons to move the show from the train to the show lot, or they carried their own gilly wagon. This was basically a skeletal wagon with removable wagon wheels. When the show was traveling, the wagon would be disassembled and shoved into any remaining space on the baggage car. Most showmen of the day knew the amount of work associated with a Gilly operation and the infrequency of the paydays and stayed away from such operations. Most of these Gilly Shows were considered “high grass” shows in the circuses and carnival business, They were shows that played the small, sparsely populated, rural towns of America. All equipment had to be torn down, loaded onto the wagon, then transported to the railcar. The wagon would then be returned to the lot to get whatever equipment was left. This process might require a half dozen trips. Once at the rail car, it would have to be reloaded from the wagon and packed tightly into the train. When the train reached the show’s destination, the whole process had to be repeated in reverse. The last of the Gilly Shows was Cooper Bros. Circus which called it quits at the end of their 1934 season.

Rail Equipment of The Old Shows – Railroad History from Circus Trains and Carnival Trains

Since the railroads charged the show by the number of cars moved, not the length or weight, the shows’ ownership built longer car lengths of 50 feet, then 60 feet, and finally 72 feet. It cost the shows the same amount to move ten 40 foot cars as it did to move ten 60 foot ones. The modern Ringling show uses flats of 85-foot length. In the heyday of the railroad show, two companies emerged as the primary suppliers of circus and carnival flat and stock cars, the Warren Tank Car Company and Mount Vernon Car Manufacturing Company. The trains coaches were used equipment purchased from the railroads or other defunct shows that had gone ‘belly up.’

In 1923, following World War I, and again in1947, after World War II, the Ringling Brothers Circus purchased surplus hospital cars from the government and converted them for circus use. The three basic types of carnival and circus railroad cars used from the 1930’s into the 1950’s were flat cars, stock cars, and coaches. Along with these cars, there were some specially modified and unique cars.

Stock cars were usually coupled directly behind the locomotive to help minimize jolting the animals, then came the flat cars which were the heaviest due to the rides and other equipment, and finally, the coaches brought up the rear of the train.

Show trains were moved in sections. Prior to WW II, RBBB had 100 cars which were moved in four sections. According to Emmett Kelly, Jr., it cost the circus about $1000 to rent the locomotive which moved each circus train section and $1.00 a mile to move the Ringling Bros. show following World War II. In 1947, RBBB traveled on 109 cars, the largest railroad circus in history. In 1949, the RBBB moved on 89 circus railroad cars which when fully loaded weighed approximately 6,850 tons. If this same equipment was moved on standard rail cars of the time, it would have required a 178 car freight train.

Railroad carnivals could be much heavier due to the weight of the rides and heavier built wagons that were primarily constructed from iron and oak.

Motive power for the show train was always provided by the railroads. What type of motive power did the railroads use to move the heavy circus trains? 2-8-2 Mikados by the Chicago and North Western Railway and Santa Fe, 4-8-4 Northerns by the Union Pacific and Milwaukee Road; the Chicago Burlington & Quincy (the Burlington ) used EMD 6000 horsepower freight diesels.

Even though circus trains included passenger coaches, they were always moved as freight by the railroads, and so, the railroad’s caboose brought up the rear.

Flat Cars – Railroad History for Circus Trains and Carnival Trains

The early flat cars, like most railroad equipment of the era, were made of wood by wagon companies or contracted in railroad shops. They required adjustable metal truss rods along the bottom to keep the sag out of the car due to the heavy loads they had to bear up under. They were a maintenance nightmare due to wear and weather and required constant attention by the train crew.

The first show flats of steel construction were sixty-foot cars. The first show to use these flats was the Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show in 1911. By the 1920’s the Warren Tank Car Company of Warren, Pennsylvania, and the Mt. Vernon Car Manufacturing Company of Mt. Vernon, Illinois, were the principal providers of the steel circus and carnival flat cars. In 1926, both these companies were competing heavily to get circuses and carnivals to convert from the 60-foot cars to their new 70 and 72 foot flats. Two other companies produced limited amounts of steel show flat cars, Keith provided cars similar in appearance to those manufactured by Warren to the Hagenbeck-Wallace and the Sells-Floto circuses in the 1920s. The other company was the Thrall Car Company of Chicago which built five flat cars in 1947 for Ringling Brothers Circus stayed with the wooden flats longer than the other circus, using them into the late 1920s, beginning the conversion to Warren flats in 1928. The last of the wooden flats, which originated with the 101 Ranch Wild West Show, were used by the Bill Hames Carnival in the 1940’s.

The 70 foot Mount Vernon flat cars can be distinguished by the pot belly sides with ribs. (see photo on right)

The 72 foot Warren flat car had no ribs and gently arcing sides on both top and bottom. A typical Warren flat car measures 73 feet over the couplers, seventy feet for the bed, and 9′ 9 1/4″ in widt h. (See photo on left)

h. (See photo on left)

Stock Cars – Railroad History Circus Trains and Carnival Trains

Stock cars were 72 feet long and of two basic types. One was designed for the horses and ring stock and the other for the elephants, or in circus parlance, “bulls.” Like the flat cars, most stock cars were built by the Warren Tank Car Company or Mount Vernon Car Manufacturing.

The cars used to transport the bulls had solid sides and small windows for ventilation near the top of the car since the elephants were susceptible to pneumonia. They were also about a foot taller than the other stock cars and had larger doors positioned directly across from each other in the center of the car. The elephants were usually positioned in three pairs at each end of the car and another elephant could be loaded at the center of the car, facing a door. Thus, each bull car could carry 12 or 13 adult elephants. If a circus did not have this many bulls, one end of the car might be outfitted with bunks for the “bullmen,” or elephant handlers.

Before tractors and trucks were in widespread use, the circus carried two types of horses. Baggage stock were the draft horses used to move the wagons between the train and the lot and in the show parade and the ring stock which were the horses that performed in the show. Rail cars which carried ring stock were equipped with individual stalls for each horse. Baggage stock did not have stalls but were loaded side by side, always in the same spot, in each end of the car. Since the baggage stock would be needed immediately at the next city, they were carried with their harnesses on. Chains were hung from the roof of the car with a hook on the end. The horse’s collar was attached to the hook to relieve the weight around its neck. The harnesses were only removed from the baggage horses at the horse tops (stable tents) on the show lot during the day. Each stock car had troughs running the length of the car so that the horses could be fed in route during long hauls. Each trough had a lid with a chain attached. The chain ran to a handle in the roof and during the trip, the attendants would walk along the roof and raise the trough lids to feed the horses. The loading ramps for cars that carried ring stock had sides, but those for baggage stock did not since the harnesses and collars had a tendency to catch the rails as the stock was loaded or unloaded. The ramps were stored on racks located under the car during a jump.

A typical stock car could carry about 27 baggage horses or 32 ring stock. Ponies and other small animals could be double-decked so that no space was wasted. If there was still extra space inside, it was used to store extra supplies of programs, tickets, and concession items. Doors on these cars were offset on each side, that is not across from each other. This permitted loading the entire length of the car with stock, no wasted space in the center of the car as there would be if the doors were directly across from each other.

Into the 1920s, most stock cars were wooden, including the ends. With the arrival of the steel flats, the ends of the stock cars became more solid as they were made from corrugated steel. The stock cars used by the Ringling Bros. today are converted from former passenger cars and are equipped with automatic, temperature controlled watering devices and air conditioning. (See Photo)

Coaches and Unique Passenger Cars – Railroad History From Circus Trains and Carnival Trains

Although a very few shows bought new coaches for their personnel, most carnivals and circuses purchased obsolete or at least, used, railroad equipment. Almost without exception, any coach coming into the shows rolling stock lineup was immediately gutted of everything that the Pullman company had installed.

The circus had a very strict employee caste system and this was no more pronounced than in personnel sleeping assignments on board the train. Featured performers and key personnel were often assigned a stateroom or perhaps even a half or third of a car. Some of the larger shows might even have a private coach for the owner or star performer (See photo), such as Tom Mix on the Cole Bros. train. The Ringling train carried two private cars, one for John Ringling, “The Jomar“, and another for Charles Ringling, “The Caledonia“. However, these were the rare exceptions. Most of the circus coaches were filled top to bottom with berths. An individual’s assignment in the circus and length of employment dictated the assigned berth. A newcomer, or “First of May” in show parlance, might be assigned the top berth. Working men might be assigned two to a bunk.  These cars were not air-conditioned and many a circus and carnival worker chose to sleep on an open flat, beneath the wagons, on a hot summer night. The same premise held true for carnivals although they didn’t have the rigid caste system of the circuses. Bosses and their families that were part of the office hierarchy such as the Ride Superintendent, Train Master or Lot Man could be assured a better stateroom appointment while the “Roughies” and “Ride Monkeys” could expect a plywood bunk in a gutted out former coach with a shared toilet at the end of the car. Since there was no air-conditioning, these coaches could usually be identified by the smell that emanated from them, especially during the hot summer months. There were no porters on most carnival trains.

These cars were not air-conditioned and many a circus and carnival worker chose to sleep on an open flat, beneath the wagons, on a hot summer night. The same premise held true for carnivals although they didn’t have the rigid caste system of the circuses. Bosses and their families that were part of the office hierarchy such as the Ride Superintendent, Train Master or Lot Man could be assured a better stateroom appointment while the “Roughies” and “Ride Monkeys” could expect a plywood bunk in a gutted out former coach with a shared toilet at the end of the car. Since there was no air-conditioning, these coaches could usually be identified by the smell that emanated from them, especially during the hot summer months. There were no porters on most carnival trains.

Coaches were assigned by circus department, for example, band members might be assigned to one car, performers and staff to another, clowns to another, and so forth. Single girls were assigned to a separate car which became nicknamed “the virgin car.”

The porter assigned to each car was not only the housekeeper but the law on the car. He enforced the rules and settled disputes. He also was the mailman and ran errands for the occupants of his car. For these duties, he was tipped quite handsomely from his “charges.”

In 1947, RBBB had taken possession of surplus hospital cars purchased from the government following World War II. These cars were converted for use by the circus. (The Monon Railroad’s coaches for trains like the Thoroughbred were also converted hospital cars.) In 1986, three of these converted hospital cars were seen in a Tampa, FL, scrap yard awaiting demolition. One of these hospital cars, Advertising Car No. 1, is preserved at the Circus World Museum in Baraboo, WI.

In later years, most of the Ringling Brothers Barnum & Bailey Circus Coaches had hot water and showers. Each had a porter assigned whose responsibility was to make up the beds and keep the car clean. One car had short berths for the midgets as well as special berths for the fat lady and giant. One car was designated for the single women of the show and had a “car mother” assigned to look after the girls; another was set up for families, and another for the single men. Unlike most other railroad shows, every working man had his own berth. The early circus coaches sometimes had berths three high; some shows had a single berth at the top of the car and a double berth below in which two workers slept.

Unique Rail Cars – Railroad History From Circus Trains and Carnival Trains

In 1936, Ringling Brothers added a hospital car, Number 99, called the “Florence Nightingale” to the circus train. This luxury traveled with the show for only one year.

In 1949, Ringling Brothers added a laundry car with commercial laundry equipment to do the shows dry cleaning and laundry.

John Ringling’s private car, the Jomar, had a cook, valet, and secretary who stayed with the car even with John Ringling was not on the show. It contained a living room, staterooms, full-sized bathroom, dining room, kitchen, and quarters for the chef and butler. This car reportedly cost John Ringling $100,000, not a small sum in 1921. Today this car can be seen, fully restored to its former splendor, as a static exhibit at the Ringling Museum in Sarasota Florida. It is an absolutely beautiful and magnificent piece of show history.

The Pie Car – Railroad History From Circus Trains and Carnival Trains

The Pie Car is the closest thing the show train has to a railroad diner or club car. The Pie Car served as the social gathering place while the train was in route. Sometimes, the operation was let out as a concession and on other shows, it was run the by the show’s management. The Pie Car offered short-order food and some had a bar. Show personnel could usually find a game of cards or dice in progress in the Pie Car. The Pie Car did not always serve full meals for the show people on many shows. One exception was the Nickel Plate Shows which had no cookhouse and fed its personnel three meals per day in the Pie Car. The Pie Cars on today’s Red and Blue Units of the Ringling Bros. Circus are dining cars and a large portion of those shows’ personnel eat their meals in the Pie Car. However, these modern day Pie Cars still offer short orders from an early breakfast to a midnight snack.

Advance or Advertising Car – Railroad History From Circus Trains and Carnival Trains

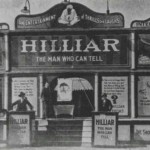

The advance car went well ahead of the show, usually as part of the back end of a passenger consist. It was usually identified by the flamboyant, bright and artistic paintwork it carried.

This car was designed to be noticed. (See photo) Its function was to alert the population in the area of the show’s arrival. The advance car, in addition to sparse living accommodations, had large wooden tables and reams of “bills” ( bright and colorful posters) that could range in size from a window card to a ‘multi-sheet’ that could cover the entire side of a building or barn. The stories regarding the escapades of the advance teams are the stuff of legends as they often pasted their bills over every surface possible despite the property owners objections.

to sparse living accommodations, had large wooden tables and reams of “bills” ( bright and colorful posters) that could range in size from a window card to a ‘multi-sheet’ that could cover the entire side of a building or barn. The stories regarding the escapades of the advance teams are the stuff of legends as they often pasted their bills over every surface possible despite the property owners objections.

“Goliath” Car – Railroad History From Circus Trains and Carnival Trains

In 1928, Ringling featured a sea elephant, named Goliath. The previous year, the Warren company had built Ringling a modified stock car for a white elephant which had been exhibited in 1927. This car had an off-center dividing wall which divided the car into a short and long end. In 1928, Ringling installed a large water tank in the short end of the car for Goliath, and filled the long end of the car with regular elephants. When Goliath was returned to the car each day, his specially built flatbed wagon was backed up to an extra door on this customized stockcar and Goliath would enter his private compartment. This specially modified car presented problems during transportation since the sloshing of Goliath in the tank and the movement of the water would cause the car to sway and frequently derail. This car was on the Ringling circus train for four years and traveled a fifth year with the Ringling owned Sells-Floto Circus train.

More history to come . . . check back often